Leah’s changed state mirrors Miri’s mother’s dementia and explores how to start grieving someone who is still alive but so irrevocably changed that it feels like a kind of death.

The novel asks: when it is appropriate to start grieving someone? When is the exact moment of loss? Before Leah returns, Miri is trapped in a sort of limbo – it feels like giving up to assume Leah is dead, to start grieving – but upon her return it feels like rejecting this new Leah, abandoning her in a time of need, to grieve the Leah she has lost. The psychological horror of the submarine chapters gives way to the body horror of the land chapters as Miri watches Leah’s body slowly transform into an oceanic horror increasingly unsuited to dry land.Īrmfield uses these overlapping timelines and perspectives to explore grief, as the narrative of Miri’s mother’s decline and death from dementia – which happened at the beginning of her relationship with Leah – and the grief Miri feels during Leah’s absence and after she returns are both uncomfortably extended.

But soon simple cabin fever gives way to something else, as Leah, Jelka and Matteo lose track of the day and night, hear banging at the submarine door, and increasingly engage in erratic and unexplainable behaviour, all heralded by a smell of burning meat upon their descent. For anyone averse to the sea or confined spaces, the prospect of a small craft sinking to the bottom of the ocean is horrifying enough. The horror in the novel centres around Leah, both her time on the submarine and after she returns to land.

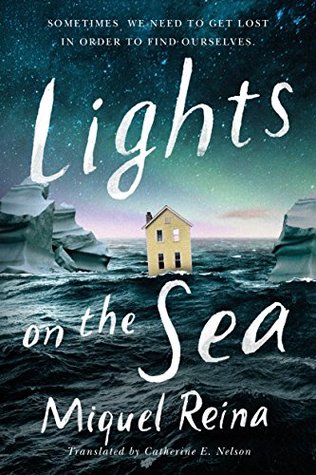

The novel makes use of multiple horror motifs: submarine entrapment in the ocean’s abyss, losses of time, hearing ghostly voices, and horrifically transformed bodies. As the story develops, the novel moves through the ocean’s vertical zones (sunlight, twilight, midnight, abyssal, hadal), with the growing darkness of these zones and the increasing biological weirdness of their inhabitants reflecting the progression of the narrative, as we see the creeping horror of the ocean brought onto land. The novel is told in two alternating perspectives and voices: Leah’s, narrating her time in a submarine during a deep-sea research mission that left her and two crewmates trapped at the bottom of the ocean after an unexplained system-failure and her wife Miri’s, as she waits and presumes Leah dead until her impossible return six months later. But, like the sea, it has unknown depths and horrors to which they will sink. The lives of Miri and Leah are as complete and furnished as a house, their minute actions and seemingly mundane memories building a complete structure of their relationship. ‘The deep sea is a haunted house’ is how Julia Armfield’s debut novel Our Wives Under the Sea opens, and the same can be said for the book itself.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)